LIVE - Rebellion Reads Posts

Omai and the Polynesian Tattoos That Changed Europe

Omai and the Polynesian Tattoos That Changed Europe

For centuries, the Western world tied tattoos to criminality and social deviance. Nevertheless, in the 18th century, one man challenged that view. Omai Polynesian Tattoos fascinated London when this Tahitian islander arrived in the 18th century, making him the first tattooed celebrity of Europe. His presence, his culture, and above all his tattoos transformed how society saw body art.

Who Was Omai, the Tattooed Tahitian in London?

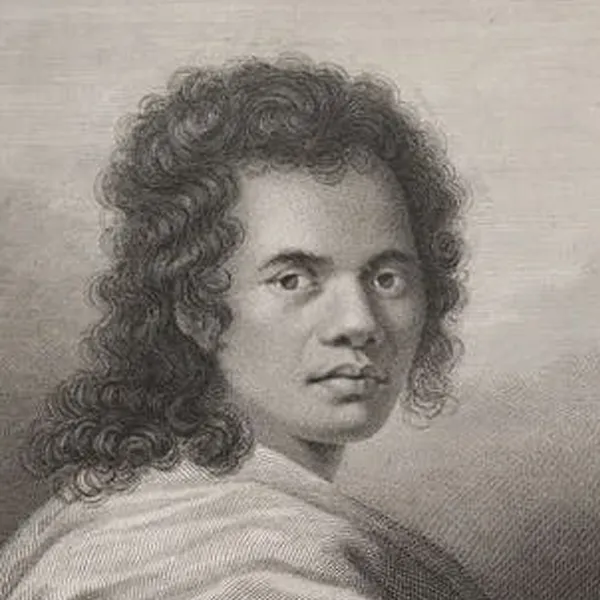

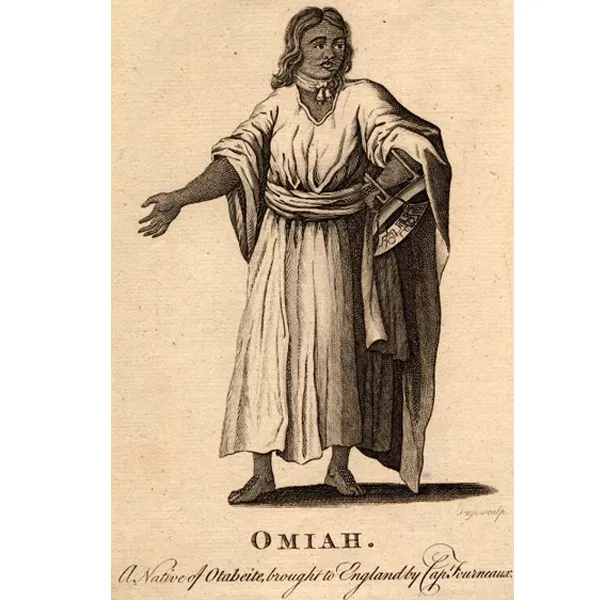

To begin with, Omai — originally named Mai — was born on the island of Raiatea, part of Tahiti. The son of a landowner, he held noble rank in Polynesian society. In 1774, he sailed to England aboard HMS Adventure, part of Captain Cook’s second voyage.

However, although Captain Tobias Furneaux brought Omai as something of a “curiosity,” the English aristocracy quickly welcomed him as their guest. His noble status at home and his composed demeanor in London elevated him far beyond the role of spectacle.

Omai Polynesian Tattoos and Their Meaning

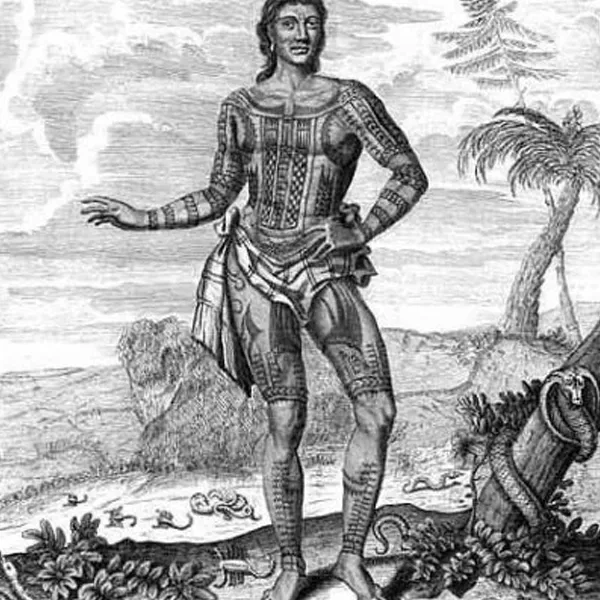

Captain Cook had already recorded Polynesian tattooing traditions before Omai’s arrival. In 1769, he wrote in his journal: “Both sexes paint their bodys Tattow… done by inlaying the Colour of black under their skins in such a manner as to be indelible.” This marked the first use of the word “tattow” in English, a term derived from the Polynesian word tatau — the tapping sound made when ink entered the skin.

In fact, in Polynesia, tattoos were more than decoration; they were a living language. Body art expressed identity, rank, and maturity. Indeed, Omai carried intricate tattoos across his back and hands, black-lined designs that captivated Londoners. To a society where tattoos symbolized crime, his ink looked fascinating, mysterious, and powerful.

Omai Polynesian Tattoos and Becoming a Celebrity

Omai’s impact went beyond tattoos. His refined manners and charisma won over England’s elite. As a result, Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, and Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, became his patrons. They introduced him to high society, arranged his residence in London, and even presented him at court.

King George III and Queen Charlotte were intrigued. Omai dined at royal tables, attended banquets, and learned to ride horses, play chess, and socialize as an English gentleman. Moreover, tall, handsome, and tattooed, rumors spread that he had affairs with aristocratic women. Consequently, his presence inspired plays, poems, and even a pantomime titled Omai: Or, A Trip Round the World. One of the most famous portraits of Omai still survives today, painted by William Hodges and preserved at the Royal Museums Greenwich.”

In a time when most visitors from beyond Europe were marginalized, Omai became a sensation — the first celebrity of Polynesian heritage in England.

The Wind of Change in Tattoo History

Omai’s story reflected the shifting tides of the Enlightenment. As Europe questioned old norms and embraced new ideas, Europe no longer dismissed Omai as uncivilized but admired him as fascinating and dignified.

As a result, tattoos that once symbolized criminality in Europe began to spark fascination. Soon after his return to Tahiti, English sailors proudly displayed their own tattoos for money in taverns. In turn, these displays spread tattoo culture further into popular life. What had been shameful marks were becoming signs of adventure, identity, and culture.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Omai’s visit to London did more than captivate high society — it reshaped how Europe viewed tattooing. His Polynesian tattoos introduced a new language of identity and rebellion that challenged centuries of stigma.

Omai Polynesian Tattoos were not just body art; they were a turning point. In the end, through one man, Europe discovered that tattoos could carry dignity, pride, and power — a legacy still alive in tattoo culture today.

Explore more in The Rebellion Reads as we uncover tattoo history and culture shaping today’s craft.